GAM Explains: The UN’s Conference of the Parties (COP) Process

07 October 2022

Each year world leaders assemble for the UN’s Conference of the Parties (COP) to take action on climate change. This year’s meeting will take place at the Egyptian coastal resort of Sharm-el-Sheikh from 6 to 18 November.

It’s worth noting that the climate COP is not the only COP. For example, there is also a biodiversity COP, which relates to a different UN convention. However, this article will focus specifically on the climate COP process and why it matters for investors.

Climate change is an archetypal example of the “tragedy of the commons”. Climate efforts must be implemented collectively by international peers to jointly address climate change and its impact.

It was the need to meet this challenge that gave birth to the UNFCCC, or the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change; the key treaty addressing climate change and signatories to this Convention involves nearly every nation across the world.

History of COP

COP stands for ‘Conference of Parties’, with the parties representing those governments which have signed the UNFCCC or subsequent agreement - 197 parties in total. The overall intention of the Convention, which entered force in 1994, is to curtail the rise in human-induced temperature and stabilise greenhouse gas emissions to “healthy levels”.

The COP is the overarching decision-making body of the Convention and subsequent agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, and is made up of government representatives from all parties in the Convention, and is also attended by civil society groups, the private sector and the media. They have met each year for almost three decades, beginning with Germany in 1995. In fact, the first ever chair of COP was the then German Environment Minister – Angela Merkel.

For many years following this first meeting, there was much discussion but no global agreement on climate targets and actions. This all changed in 2015, when countries agreed on the Paris Agreement at COP21 – the first legally-binding global treaty on climate change.

Commitments included:

- Keep the rise in global average temperature to ‘well below’ 2°C, and ideally 1.5°C, above pre-industrial levels.

- Strengthen the ability to adapt to climate change and build resilience.

- Align finance flows with ‘a pathway towards low greenhouse gas emissions and climate-resilient development’.

The Paris Agreement gave the world the regulatory and political directional clarity to take action and to begin to invest at scale in the low carbon transition. This was an enormous milestone and success for COP21.

While the Paris goals are collective, individual countries have their own targets to contribute, called Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs). NDCs are national climate plans in which each country offers a clear direction for how they will limit emissions and increase resilience to the effects of climate change. These are tangible, time-bound targets which must be reviewed and reset every five years. For example, by 2030, the UK has pledged to cut emissions by at least 68% from 1990 levels1 and India is committed to transforming 50% of all its energy to renewable sources.2

Last year’s conference – COP26

COP26 in Glasgow last year marked the first milestone since the Paris Agreement where most countries submitted revised NDCs. While over 120 governments submitted new or updated NDCs, the new targets were insufficient to meet the well below 2°C target, with estimates putting the projected impact at 2.4°C.3 However, the Glasgow Climate Pact, referenced ‘accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies’ and over the course of COP26, a number of multilateral pledges were made (across governments and the private sector) on issues such as deforestation and methane.

Climate change poses a systemic risk to the global economy, environment and society. The COP process, associated commitments and policy measures announced by parties to COP shape the landscape for investors to navigate and drive the low carbon transition. The ambition and coherence (or lack thereof) of government policy supporting a sustainable transition of key sectors and systems, such as energy and transport, will be critical in whether the transition delivers not just on the temperature goals but also on the extent of social and economic impacts of the transition.

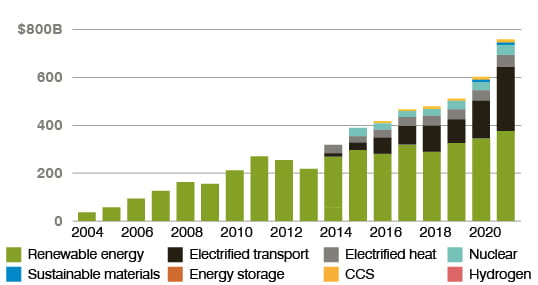

The transition also presents unprecedented opportunities. It means whole new sectors will likely expand rapidly, such as renewable energies, biofuels, green transportation, waste reduction and sustainable food production to name a few, providing investors with vast opportunities to ignite growth in new industries. From plant-based meats to plastic waste systems, new low carbon products and innovations are coming on stream and attracting interest from financial markets. We believe the private sector is uniquely placed to spur green growth. Global investment in the energy transition hit USD 755 billion last year4, and these opportunities are only going to grow. Recent analysis estimates a cumulative climate investment opportunity of USD 24.7 trillion in emerging market cities by 2030.5

Figure 1: Low-Carbon Investment

What is GAM doing?

GAM Investments strives to be at the forefront of the climate agenda and has committed to supporting the goal of net zero emissions by 2050 by joining the Net Zero Asset Managers initiative. This includes setting interim targets on engagement and decarbonisation by 2030.

We launched our Sustainable Climate Bond strategy last year, one of the first to focus on green bonds issued by European financials, to support decarbonisation.

Our Global Head of Sustainable and Impact Investment, Stephanie Maier is also a member of the global Steering Committee of Climate Action 100+, one of the world’s largest investor collaborations, which has encouraged 52% of the 160 highest emitting companies in the world to commit to net zero by 2050.

1) The race to cut carbon has got off to a slow start

The world emitted 36.3 billion tonnes of carbon last year6. That’s the highest amount ever recorded in history. Average annual emissions between 2010-2019 grew7 across all sectors, and one influential study indicates that even if all NDCs are implemented, the world is still on track for close to 2.4˚C of warming.8

So, there is a long way to go to fulfil the aspirations of the Paris Agreement. All sectors of the economy require significant transformation to meet decarbonisation targets.

2) Finance remains critical

As international cooperation is the bedrock for meaningful climate action, all countries must play their part in reducing emissions in line with the goal to limit warming to well below 2˚C. All have different starting points, however, and not all have the economic and technological resources to do so.

COP3 in Kyoto (1997) was the first conference to recognise developed countries as responsible for the majority of man-made global warming. This laid the ground for commitments in the Paris.

Agreement, where wealthier nations pledged to provide more finance to poorer countries for climate mitigation and adaptation, promising at least USD 100 billion a year by 2020.9

Progress is happening. Funding from the developed world is assisting developing countries. This can be seen in Zambia where the UN’s Green Climate Fund is helping smallholder farmers adapt to deteriorating climate impact, or in Cambodia where efforts in developing solar power and other renewables have been introduced. While such steps are encouraging, finance mobilised for emerging and developing economies is still nowhere near the level needed.

It’s a similar story for financial markets. Financiers declared a deluge of targets at COP26 to finance emission cuts, with 29 of the 30 largest financial institutions setting goals of net zero emissions by 2050 or earlier as part of the GFANZ initiative. Yet there is a large gulf between long-term goals and the finance already provided. As capital markets hold the purse strings to accelerate the transition to a low-carbon economy, it is imperative that investors meet their promises and make forward-thinking decisions based on the risks and rewards ahead.

There is also the need to ensure the low carbon transition is a fair one. This process – badged as the ‘just transition’ – means ensuring that economic transformation happens in a fair way, leaving no one behind, providing alternative opportunities for coal mining communities, livestock farmers or others impacted by the low carbon transition.

3) Accelerating adaptation is a necessity

While significant focus is given to mitigation, adaptation is equally critical, with fires, floods and storms becoming a reality for millions of people across the planet.

Landmark IPCC report in February – Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability – shone a spotlight on the world’s need to adapt as the research underlined the certainty of increases in extreme weather events.

It showed the devastating social and economic impacts the world faces. In Europe, for example, by the end of the century, as much as USD 12 billion in assets and up to 510 million people will be exposed to coastal flood damage.10 Even if the world meets its targets, some of the damage caused already is irreversible, and so this means we need to invest in adapting areas such as infrastructure and land use to protect and strengthen nature and society.

The IPCC highlighted successful adaptation projects so far, including low-carbon and reliable public transport networks, the development of resilient new buildings and local renewable energy generation. Despite this, a major conclusion from the report is that progress on adaptation is happening too slowly, leaving more than half the population (3.3 billion people) “highly vulnerable” to the impacts of climate change and many parts of the planet “unliveable”. If we want to build resilience to the impacts of climate change, there must be a concerted effort to target finance to effective adaptation approaches.

COP27 in Egypt later this year will be pivotal in how the world responds to climate change. The current energy crisis amid Russia’s invasion of Ukraine threatens to undermine climate policy progress and obstruct the shift away from fossil fuels, with countries including the UK and Germany scrambling to find new sources of oil and gas. It is vital that we stay on track to meet the longer term targets in line with the Paris Agreement and refocus national plans to clean, sustainable energy systems, while recognising the immediate energy security and affordability challenges. There is an expectation that updated NDCs will be submitted for a number of countries – the extent of these will be closely watched.

A key theme at COP27 will be assessing collective progress since the Paris Agreement. There are also hopes for climate injustice to be a main focus, especially given the conference will take place in Africa which contributes less than 4%11 of the world’s energy emissions yet stands to suffer greatly from rising global temperatures. We can also expect to hear updates from the financial coalitions who made promises last year, such as GFANZ.

Government policy and finance will remain critical to the pace and progress of the transition. Climate risks and opportunity will continue to shape the investment landscape. COP27 provides an important staging post on how orderly or disorderly that transition will be.

To learn more about the findings of each COP conference, visit the UN’s website here.

For more insights from GAM, go to ‘Our Thinking’ page here.

2https://climateactiontracker.org/climate-target-update-tracker/india/2021-11-01-2/

3https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/

4https://about.bnef.com/energy-transition-investment/

5https://www.ifc.org/wps/wcm/connect/topics_ext_content/ifc_external_corporate_site/climate+business/resources/green+buildings+report

6https://www.iea.org/news/global-co2-emissions-rebounded-to-their-highest-level-in-history-in-2021

7https://www.unep.org/news-and-stories/story/wake-call-humanity-qa-climate-expert-ipcc-report

8https://climateactiontracker.org/global/temperatures/

9 https://unfccc.int/news/un-climate-chief-urges-countries-to-deliver-on-usd-100-billion-pledge

10https://www.ipcc.ch/report/sixth-assessment-report-working-group-ii/

11https://unfccc.int/news/africa-climate-week-2022-set-to-harness-opportunities-for-climate-action-ahead-of-cop27

The information in this document is given for information purposes only and does not qualify as investment advice. Opinions and assessments contained in this document may change and reflect the point of view of GAM in the current economic environment. No liability shall be accepted for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results or current or future trends. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. There is no guarantee that forecasts will be realised.