Since the global financial crisis in 2008 US equities have significantly outperformed their counterparts from the rest of the world. GAM’s Global Head of Investments David Dowsett believes investor engagement with non-US assets could come to the fore this year as part of a long-term structural shift.

15 March 2023

Regular readers will know I am of the opinion that 2022 represented a structural break in the investment environment. The zero-interest rate policy experiment is now decisively behind us. The pandemic and the Russia/Ukraine war have ended the era of increasing and unquestioned globalisation.

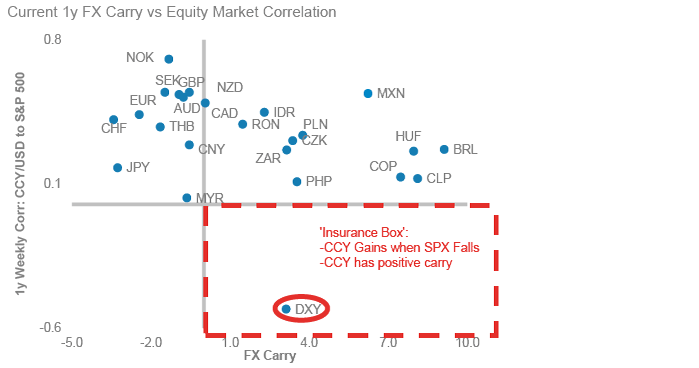

Many asset classes suffered extreme corrections in 2022, but one feature of the previous investment environment persisted; the US dollar continued to appreciate, building on the relative gains it had experienced throughout the zero-interest rate period. As the chart below shows, the dollar benefited in 2022 from being both a high carry and a safe haven currency.

Chart 1: US dollar strength (DXY) has been boosted by the perception of the dollar as a safe haven

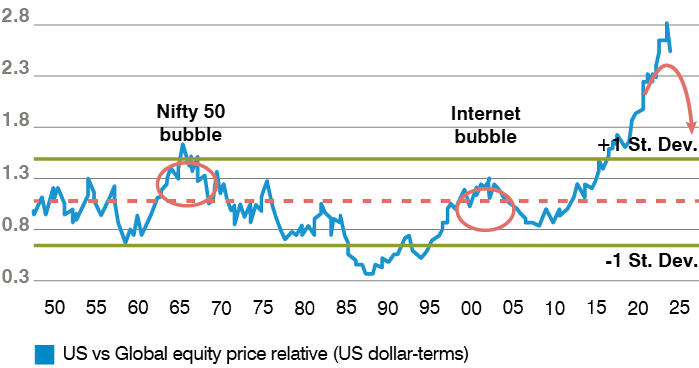

Since October last year that trend has begun to change. We believe the recent reversal of fortunes for the dollar may signal the beginning of a much more significant shift. As the chart below shows, the outperformance of US assets, associated with the rise of the dollar, has been profound over the past decade.

Chart 2: Unprecedented accumulation of capital in US market

In very simple terms, USD 100 invested in US equities in mid 2008 is now worth USD 290, whereas USD 100 invested in non-US equities now worth only USD 95 (source: Bloomberg, as of 28 February 2023). Any change in this environment will have significant investment implications for every asset allocator.

We will consider the case for non-US assets according to shorter-term considerations, meaning those likely to be the key drivers in 2023, and also examine some indicators suggestive of a longer-term structural change.

- The outlook for 2023

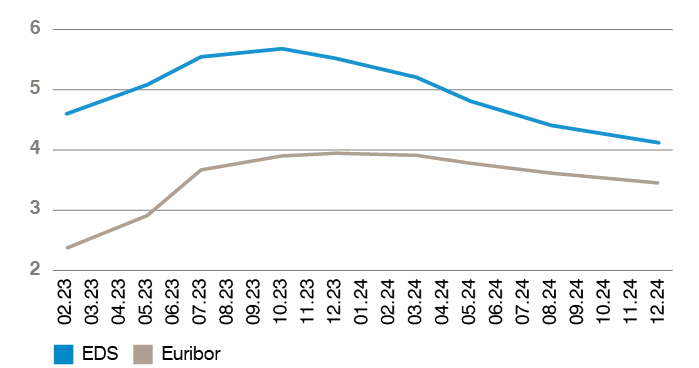

- a) Interest rate differentials. In 2022 the Federal Reserve (Fed), at least in the developed world, began the interest rate normalisation process first and moved more decisively towards its terminal rate. As the chart below shows, this pattern will probably reverse in 2023.

Chart 3: Interest rate pricing for US (EDS) and EU (Euribor) until end of 2024

The rest of the developed world is likely to raise interest rates more than the US, and so narrow the difference in the eventual predicted equilibrium rate. If we consider the difference in predicted interest rate pricing illustrated by short-term interest rate markets in Europe and the US, the difference in expected interest rates by mid-2024 is only 110 basis points (bps), far away from a current cash differential of 2.5%. This would reduce the relative carry attractiveness of the dollar, which had been a key short-term support in 2022.

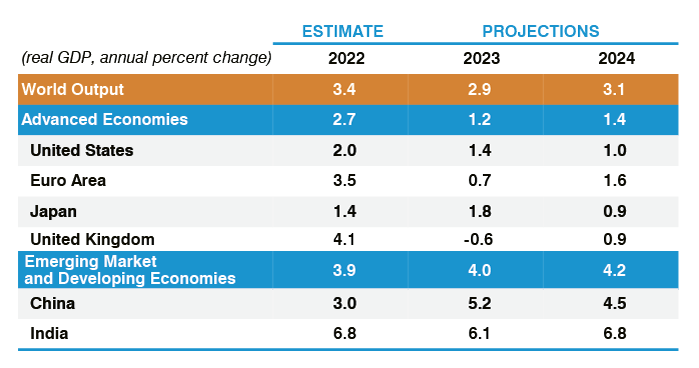

- b) Growth rebalancing. As the chart below shows, in 2023 the projections for global growth do not change too much, but the regional breakdown of where the growth impetus comes from changes dramatically with a clear shift away from developed markets (DM), in particular the US, and towards emerging markets (EM).

Chart 4: Latest World Economic Outlook Growth Projections

As the developed economies slow, growth is projected to recover strongly in Asia, most particularly in China as the country emerges from zero Covid. Other major EM economies, with their traditional China growth sensitivity, should also benefit accordingly. As we will argue below, this should lead to global investors rethinking excessively US-focused investment portfolios.

- c) Regime change in Japan.

As most central banks began to normalise interest rates in 2022, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) remained committed to zero interest rates and yield curve control. Even here, though, the sands are beginning to shift. Central bank governor Kuroda surprised the market in December by widening the band of tolerance to 50 bps either side of its 0% yield target for 10-year bonds. It now seems likely that we will get further signs of interest rate flexibility after the expected change of central bank governor in April. Prospects of higher interest rates in Japan should add support to the yen, whose chronic weakness has been an important part of the dollar strength story. Of course, higher interest rates are not intuitively supportive of other Japanese assets, but it is worth reflecting that since the BoJ introduced zero interest rates in 1997 the average annual growth outturn of the Japanese economy has been 0.1%! There could be no more demonstrative example of the effect of the adverse consequences of the great zero interest rate experiment.

- d) The debt ceiling debate.

As we discuss in more detail when thinking about the long-term prospects for the dollar below, the US faces significant debt and deficit challenges for the long term. One definite way not to solve them, however, is to default on your debt in the short term. There is obvious hesitation in making any political predictions on how the internal dynamics of the Republican Party will play out, although we saw over the impasse of the election of the speaker how far certain members of the House are prepared to go and the lack of regard for the advice of the “establishment”. The debt ceiling debate is likely to come to a head between June and August. Even if, as is probably most likely, a temporary solution is found at the last minute, it is likely to involve noise and brinkmanship. On a relative basis, this seems less favourable for the US dollar and US assets more generally.

- e) Relative valuation

Given all of the above, we can build a picture that suggests a reversal of cyclical US strength persisting throughout 2023. This is an important consideration for all asset allocators.

- The case for medium-term dollar weakness

As Chart 2 above shows, however, dollar strength has not just been a short-term phenomenon.

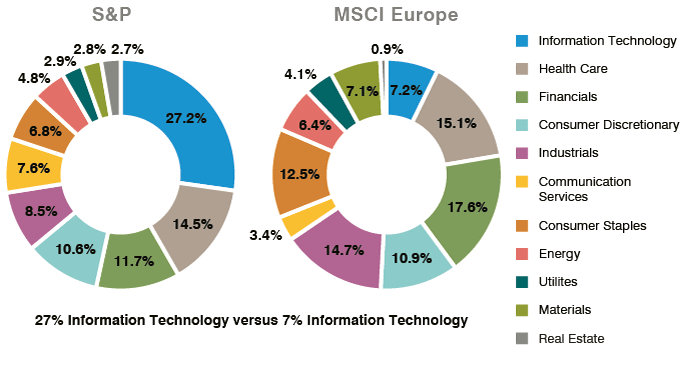

Since the beginning of zero interest rate policy post the financial crisis in 2008, we have seen close to a 3 standard deviation move in favour of US dollar assets. The era of globalisation has been accompanied by a connectivity revolution driven from Silicon Valley. Technology companies promising profits in the future have become more attractive investments as the price of time has become distorted. The dollar has also benefited from the increased financialisaton of “ideas” rather than “things”.

The structural changes that will occur as the world becomes more regionalised and focused on resilience and security, rather than efficiency and capital gain, are likely to lead to more focus on real world (or if you like old world) assets. This is not to downplay the search for continuing technological gain, but it will not be the only source of profitable investment over the next decade.

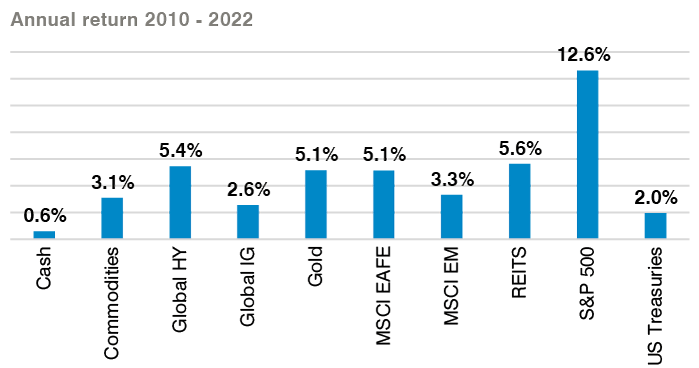

Chart 5: Annualised returns from assets 2010 to 2022

These real world assets, by definition, are based more significantly in other countries than the US. The focus of global government policy will be on rewarding those who live on Main Street, not Wall Street. This involves a fundamental rewiring of the structure of global economies that will raise the prospective return on investment within the real economy, rather than the previous excess focus on financial assets.

Chart 6: US stock market bias to technology vs other indices

This is worth considering in the case of the US dollar. The dollar has remained strong despite growing twin deficits (of which more later) precisely because we have lived in a demand deficient world. When there is no attractive real world investment opportunity global capital is recycled into financial assets, and the US is the obvious beneficiary with the world’s deepest and most liquid capital markets. As this balance changes, so the capital flow picture will change accordingly. The recent bank failure at Silicon Valley Bank and consequent weakness in the regional banking sector also reminds us that increased exposure to capital markets brings risk as well as reward. Stronger regulatory protection has held back non-US financial assets over the past decade, but perhaps will now be seen as a prudential virtue.

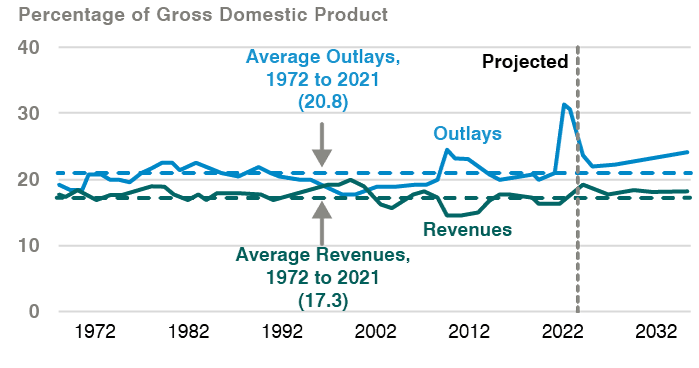

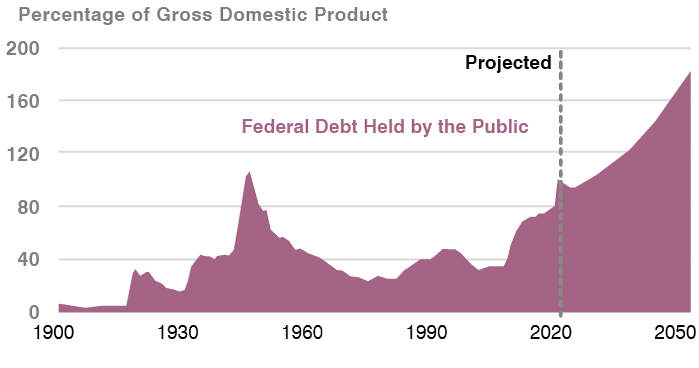

Additionally, while most of the short-term focus over the debt ceiling may involve political grandstanding on Capitol Hill, it might also prove the catalyst to focus on the longer-term weakness associated with ever growing indebtedness. Many countries have experienced a surge in long-term indebtedness since 2008, but the US has been particularly able to use the “exorbitant privilege” of global reserve currency status to increase fiscal expenditure without being subject to market discipline. US annual interest payments have averaged only approximately 1.5% of GDP during the period of zero interest rates, despite a growing slate of seemingly untouchable entitlement commitments. As the two charts below show, a continual gap between projected outlays and revenues against an expected backdrop of higher expected real interest rates only ever ends in an increasingly scary forward-looking debt/GDP profile.

Chart 7: US Total outlays and revenues

Chart 8: US Federal debt held by the public, 1900 to 2052

Although still some way in the future, the Congressional Budget Office projects that by 2031 entitlement payments, mandatory outlays and interest payments will exceed government revenues. That is a definite crunch point. To repeat, the US is far from the only country to face such a debt challenge, but it is the only one that currently exhibits such a cavalier attitude, at least among the political class, to maintaining full faith and credit, just when its reliance on the market is about to significantly increase. Of course fiscal reform is always possible; this is the professed aim of some elements of the Republican Party in Congress, although its record in government does not support its claims of fiscal rectitude. The problem becomes even more acute when set against the political trends for more active industrial policy and increased defence spending, both of which are likely to be vote winners for the rest of the decade.

It could be tempting to extrapolate these shorter- and longer-term arguments into calling for the end of the dollar’s reign as the global reserve currency. Indeed in some ways this is overdue. The average tenure of the previous five reserve currencies has been 94 years, and their eventual decline has always been signalled by imperial overstretch and increasing indebtedness. The dollar has now been the world’s pre-eminent reserve currency since the end of World War 1. It equally seems arrogant to claim to be able to exactly forecast the demise of such a long run. We will settle for highlighting the fact that some of these underlying fiscal weaknesses seem to have been forgotten during the period of zero interest rates, a period when they were actually becoming more acute. Any reconsideration of these issues can cause a more general reassessment of the prevailing wisdom of global asset allocators to be excessively concentrated in dollar assets. I think this will be a very important driver of returns for asset prices in 2023… and indeed beyond.

Source: GAM, unless otherwise stated. The information in this document is given for information purposes only and does not qualify as investment advice. Opinions and assessments contained in this document may change and reflect the point of view of GAM in the current economic environment. No liability shall be accepted for the accuracy and completeness of the information. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future results or current or future trends. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. There is no guarantee that forecasts will be realised.

References to indexes and benchmarks are hypothetical illustrations of aggregate returns and do not reflect the performance of any actual investment. Such indices are provided for illustrative purposes only. Indices cannot be invested in directly, are unmanaged and do not incur management fees, transaction costs or other expenses associated with the investments and investment strategies. Therefore, comparisons to indices have limitations and there can be no assurance that an investment will match or outperform any particular index or benchmark.

This document contains forward-looking statements relating to the objectives, opportunities, and the future performance of the U.S. market generally. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of such words as; “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “should,” “estimated,” “potential” and other similar terms. Examples of forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, estimates with respect to financial condition, results of operations, and success or lack of success of any particular investment strategy. All are subject to various factors, including, but not limited to general and local economic conditions, changing levels of competition within certain industries and markets, changes in interest rates, changes in legislation or regulation, and other economic, competitive, governmental, regulatory and technological factors affecting a portfolio’s operations that could cause actual results to differ materially from projected results. Such statements are forward-looking in nature and involve a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and accordingly, actual results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. One should not place undue reliance on any forward-looking statements or examples. None of GAM or any of its affiliates or principals nor any other individual or entity assumes any obligation to update any forward-looking statements as a result of new information, subsequent events or any other circumstances. All statements made herein speak only as of the date that they were made.