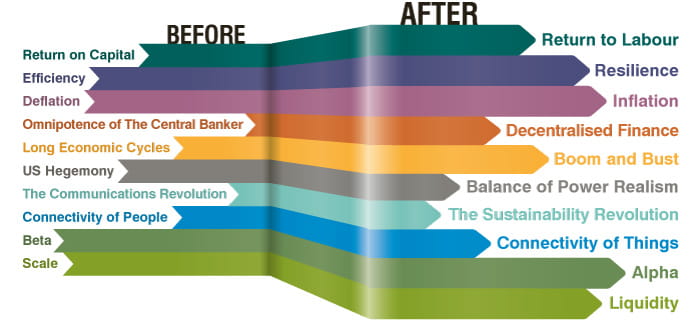

Earlier this summer Global Head of Investments David Dowsett identified 10 key investment themes where he sees a clear “before and after” effect for the 2020-2022 crisis period. In this follow up article he explores in greater detail three of these themes, which have come to dominate market pricing in 2022.

20 September 2022

- The inflation surge: The extent of this year’s increases has been dramatic. We should expect the challenge for central banks to be to ensure inflation is as low as their inflation target, rather than the undershooting of the past decade. This has obvious implications for asset class performance.

- The need for resilience: Most initial reflections around the transition from a focus on efficiency to resilience concentrated on a reduced exposure to global industrial supply chains due to heightened geopolitical risk. This has now been usurped by a focus on the needs of governments to feed and keep their populations warm; this is a basic necessity for a resilient society.

- Returns to labour over returns to capital: Policy incentives have definitively changed. For 40 years, globalisation was largely seen as an inevitability. The direction of fiscal and monetary policy was designed to support openness, low inflation, fiscal discipline and prioritise returns on capital. Today, the emphasis in the developed world remains firmly on supporting the domestic worker and promoting national resilience rather than worrying about the cost.

David also examines the investment implications of these themes and how investors should react when confronted with such a changing world.

2022 has proved an absolute brute for financial markets. At the end of H1, on an annualised basis, US equities were on track for their worst year since 1872, and US bonds for their worst year since 1865. The summer rally has lessened the pain somewhat, but it has not erased the questions surrounding global markets and how investors should position their portfolios. In our previous article “A Pandemic and A War” we made the case that those twin crises represented a decisive full stop to the era of globalisation and low inflation. As represented below, we believe investors need to take into account 10 key themes in the global economy and financial markets, and adjust their thinking about how to achieve satisfactory returns accordingly.

As this year has progressed, it has become clear that some of these trends are developing very quickly and in a more dramatic, and potentially dangerous, fashion than we had previously anticipated. We are experiencing what is known in German as a “Zeitenwende”, an epochal shift. We are seeing the world being remade politically and economically, with the trends beginning now set to last for the rest of the decade. It is essential for investors to understand these changing times in order to make the most effective strategic investment decisions.

In this article we will examine in more detail three of these trends, which have come to dominate market pricing in 2022. We believe the dramatic surge in inflation pressure and the need for nations to ensure resilience in supply chains in basic food and energy should be more fully explained. These trends in turn are reinforcing the key structural turn incentivising governments to prioritise returns to labour over those to capital. This is a decisive, and now likely irreversible, change in the policy orthodoxy that has prevailed for the last 40 years.

As described above, these developments have so far caused immense damage to financial assets. In all likelihood this volatility will persist for the rest of the year, in our view. It is also true, however, that market falls have created significant opportunity. If we are able to understand the way the world is changing, we can aim to confidently benefit from this value creation. There are certain strategies that are likely to be well placed to take advantage of this alpha opportunity, utilising the relevant experience and expertise of investment teams.

The Inflation Surge

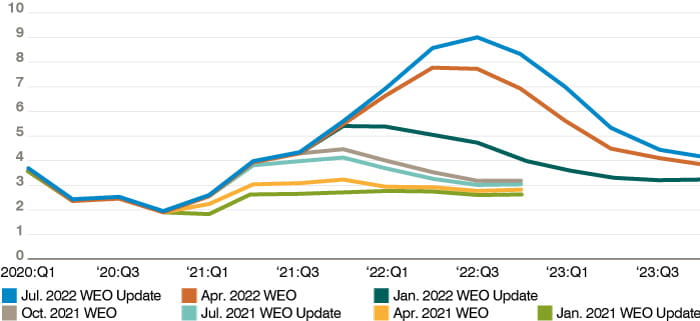

Chart 1. Global inflation forecasts: serial upside surprises

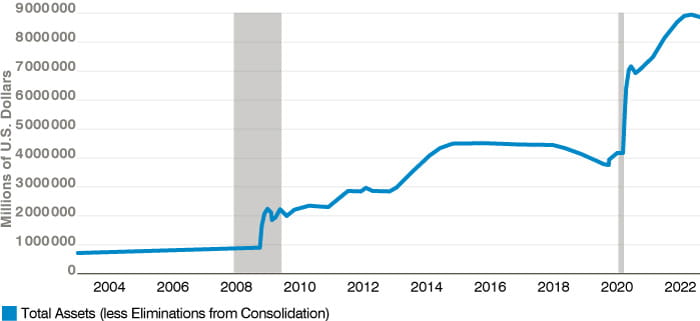

Chart 2. Fed balance sheet 2002-2022

The chart above shows the expansion of the Federal Reserve (Fed) balance sheet over the past 20 years. Remember that in March 2020, the Fed bought over USD 600 billion of US treasuries and mortgage-backed securities in a week. Globally, we had an exceptional provision of liquidity and direct fiscal support. At the same time, lockdowns suppressed normal demand and global supply chains were disrupted. An attempt was made to try to turn the global economy off and then on again without any price effect. Success was always unlikely.

Real wages in the developed world are starkly negative and there is a sense among workers who have largely been losers from globalisation that now is “payback time”. Unemployment may rise, but reduced immigration gives the domestic worker more leverage. Central banks are beginning to lean against the tide, but the Fed currently projects that it can get inflation under control with unemployment rising to only 4.1% by 2024. This seems unrealistic. The Bank of England’s more realistic projections were instantly decried by the political class as too gloomy. The tone of political debate is not one of austerity. Government policy is orientated toward more fiscal support for workers, and, in an echo of the early 1970s, price controls. In a change to the pre-pandemic era of the omnipotence of the central banker, changes in mandates are now likely to be become a more frequent topic of debate.

We do not think inflation will remain at the elevated levels currently experienced, but neither will it decline to the consistently low levels witnessed before the pandemic. We should expect the challenge for central banks to be to ensure inflation is as low as their inflation target, rather than the undershooting of the past decade. This has obvious implications for asset class performance. The concept of the “Fed put”, with central banks riding to the rescue of financial markets with ever increasing liquidity support, can only be legitimate in a deflationary environment.

The Need for Resilience

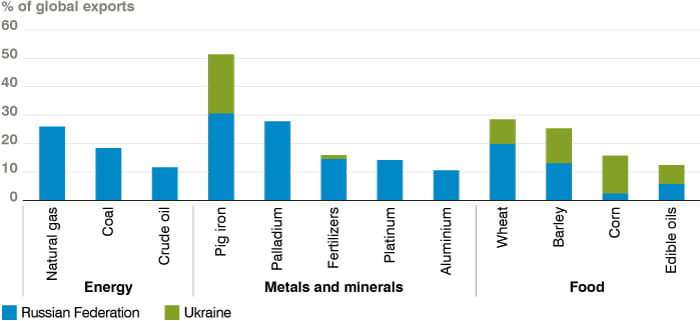

The inflationary challenge has been exacerbated by the war in Ukraine, which has put at risk a significant proportion of the world’s food and energy supplies.

Chart 3. Russian Federation’s and Ukraine’s commodity exports

Sources: World Bank Global Economic Prospects Report (June 2022); Bloomberg; Comtrade (database); IEA (2022); World Bank. For illustrative purposes only.

Most initial reflections around the transition from a focus on efficiency to resilience concentrated on a reduced exposure to global industrial supply chains due to heightened geopolitical risk. It is clear that this has now been usurped by a focus on the needs of governments to feed and keep their populations warm; this is a basic necessity for a resilient society. This tension will manifest itself in different ways. Europe’s vulnerability is particularly acute in energy.

Post-nationalist Europe has outsourced energy provision to Russia, trade to China and security to the US. How it resolves these vulnerabilities (and contradictions) will be its defining story for the next decade.

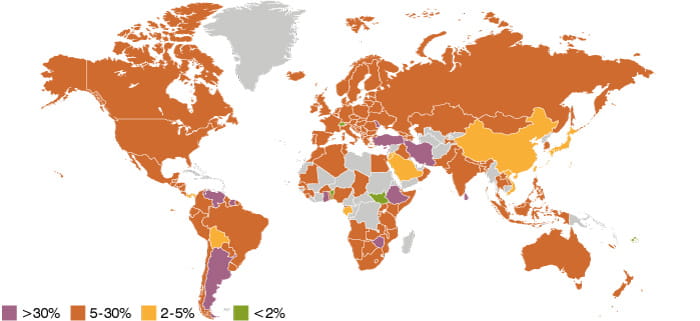

In the developing world, food price rises (shown below), will create significant risk of social unrest and political violence, such has already been seen this year in Sri Lanka. Remember that the Arab Spring was originally triggered by higher food prices.

Chart 4. World Bank global food inflation heat map (in %)

We should appreciate that the worst could be yet to come. The deficit in globally traded grain could reach 40 million tons in 2023, which equals 10% of global supply1. This poses a direct risk to the calorific intake of 250 million of the world’s poorest people.

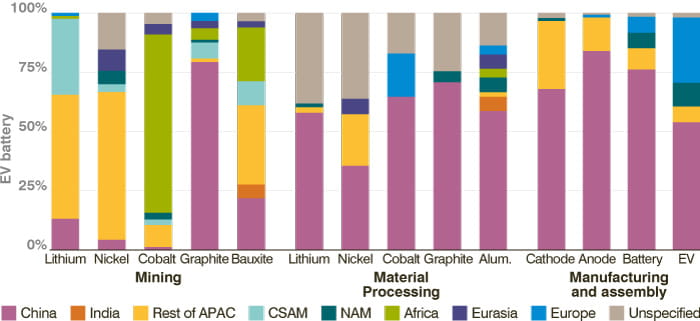

The response of governments to a scarcity of basic resources will, in my view, be exactly the same as that which we witnessed with vaccines; they will stockpile. As the chart below shows, China has already been doing this with clean energy material.

Chart 5. Geographic concentration of clean energy technologies by supply chain stage and country/region, 2021

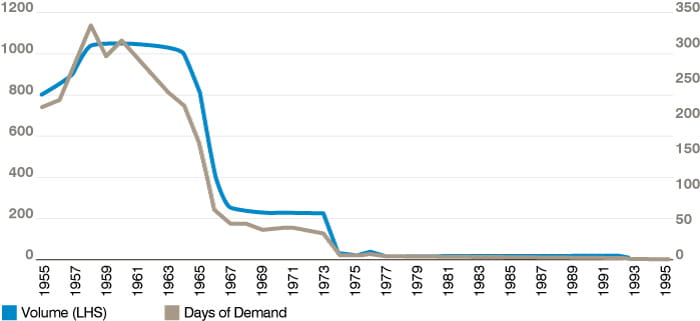

We should expect the competition for access to basic resources to grow. Competition for access to food, energy and resources is set to be a key geopolitical battleground for the next decade. It seems unrealistic that the US, for example, can remain as relaxed as it has been about copper inventories falling to the level illustrated below. Once again, this is just history returning as the Pax Americana recedes.

Chart 6. US copper inventory

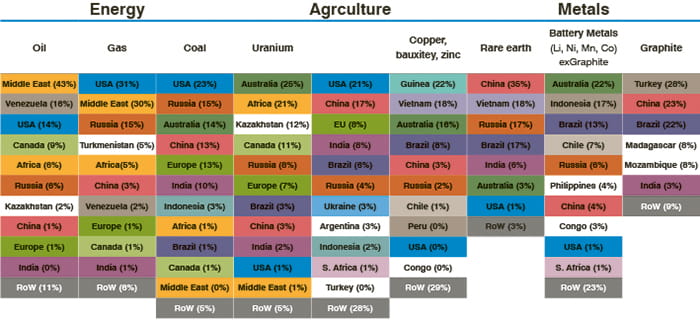

The chart from J.P. Morgan below which shows the global location of most major commodity deposits and agriculture, serves as a fascinating power map for the 2020s. This is certainly a very different way of thinking about the global economy than simply viewing everything through the lens of capital and efficiency. If these trends come to pass, they clearly have significant ongoing inflationary implications.

Chart 7. Commodity quilt

Returns to Labour Over Returns to Capital

The central thesis of the epochal shift we are witnessing is that policy incentives have definitively changed. For 40 years, globalisation was largely seen as an inevitability. The direction of fiscal and monetary policy was designed to support openness, low inflation, fiscal discipline and prioritise returns on capital.

As inflation skyrockets in 2022, there is little appetite for a hairshirt approach. Central banks have been slow and hesitant to address the inflation threat. Even more importantly, government policy shows no sign of leaning against the tide. In the developed world, the emphasis remains firmly on supporting the domestic worker and promoting national resilience rather than worrying about the cost. The mindset first introduced during the pandemic with the CARES Act in the US and European furlough schemes still holds sway.

In the UK, newly appointed Prime Minister Liz Truss recently announced a stimulus package in response to. The full cost of the package is due to be laid out by Finance Minister Kwasi Kwarteng later this month, but it is expected to reach up to GBP 100 billion, close to 5% of GDP and exceeding the cost of the UK furlough scheme. This is seen as a necessary cost to protect the domestic workforce. Similarly, the signature policy of Truss has been to propose GBP 50 billion of tax cuts, despite the fact that UK debt to GDP has already risen by 20 percentage points since the beginning of the pandemic.

The talk of nationalisation of key service providers is also growing. This is a Europe-wide phenomenon; witness the French nationalisation of EDF and the German government taking a stake in Uniper. The privatisation wave in the 1980s that was so emblematic of the prioritisation of the interests of capital is likely now to see further reversal.

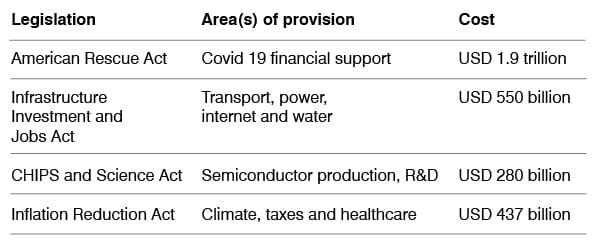

The US has seen a particularly striking degree of government intervention since the onset of the pandemic. This began with the direct distribution of government cheques to all taxpayers in the CARES Act, signed into law under a Republican administration. The Biden administration has been even more active as the summary of “Bidenomics” below shows (as at 31 August 2022).

Although much of this support is designed on a multi-year basis, it still totals 12% of GDP. As they are the most recent initiatives, perhaps the CHIPS Act and the Inflation Reduction Act are worth looking at in more detail. The name of the latter is misleading, as it will have no meaningful impact on inflation over any timeframe. In combination, these bills of legislation are an active attempt to create an industrial policy for semiconductor production and research and development (R&D), battery development and rare earth supply chain support. We will not enter into a debate on the likely efficacy of these attempts here, merely note how different this policy direction is from that which drove globalisation, an era which led to 90% of global semiconductor production to occur solely in Taiwan. The flavour here is to develop domestic jobs to help support national resilience, as driven by government incentives. Once again, the cost of these initiatives is not a source of political controversy.

It may also be worth reflecting here that these bills signify the need for greater fixed capital investment to boost the physical productive capacity of the developed world. This was neglected during the era of globalisation. Much physical capacity was outsourced to the developing world, while the West obsessed with tech. This pattern may now reverse, which has its own implications for bond yields. Additionally, all of the issues raised above suggest, in both labour and resources we now live in a supply constrained world. This is a completely different policymaking environment to the post-2008 period when a lack of domestic demand was the primary concern.

What are the investment implications?

The most important question we face is how should investors react when confronted with such a changing world?

The key point to stress is that this world is not worse, just different. One can also argue that we are likely to return to a more normal investment environment and that the previous period of low yields, low volatility and unconstrained capital flows will, in hindsight, be seen as the exception. It is, for example, entirely healthy that fixed income has reverted to being a positive yielding asset class that offers a relevant solution to savers. We have listed below what we believe are the key factors to take into consideration when considering how to deploy money in the new investing environment.

- Liquidity Matters. The new investment environment will require flexibility and pragmatism. Avoid strategies where liquidity constraints preclude portfolio repositioning.

- Experience Matters. The new environment is different but not unprecedented. Arguably, the world is returning to “normal”. Choose managers who have long track records and deep asset class expertise.

- Valuation Matters. As we move away from zero interest rates, traditional valuation metrics will regain relevancy. Choose managers with robust valuation frameworks.

- Alpha Matters. Central bank liquidity provision has driven increasing asset class correlation, and the prevalence of the “risk on/risk off” trade. Normalised financing conditions imply more single name differentiation. The emphasis returns to the skill of the active investment manager, not the beta of the asset class.

- Alternatives Matter. Increasing performance differentiation allows opportunities on the long and the short side. Examine uncorrelated performance drivers.

- Thematic Strategies Matter. It may be time to re-examine traditional asset class categorisations. The traditional bond/equity split may be less relevant. Choose strategies directly exposed to the world being remade.

We at GAM believe the future lies with high conviction, high alpha strategies. We do not offer solutions for all areas of financial markets, but we consider ourselves deep subject matter experts in those areas where we choose to focus on behalf of our clients.

The information in this document is given for information purposes only and does not qualify as investment advice. Opinions and assessments contained in this document may change and reflect the point of view of GAM in the current economic environment. No liability shall be accepted for the accuracy and completeness of the information. There is no guarantee that forecasts will be achieved. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice. Assets and allocations are subject to change. Past performance is no indicator for the current or future development.