Artificial intelligence (AI) is one of the most disruptive technologies of our time, but some of the AI-driven stocks are finding their valuations hard to justify. GAM Investments’ Mark Hawtin examines the AI capex bubble, citing examples from history of when a “build it and they will come” approach led to irrational exuberance and losses for many investors, but ultimately some long-term gains for disruptors.

02 November 2023

Click here to view the full Disruptive Strategist Newsletter.

In the 1800s the UK saw a railroad bubble driven by intense speculation in railway shares, which reached its peak in 1846/47. The belief that railways would revolutionise transportation and trade, and the availability of cheap credit, led to track being laid at a rapid pace, increasing from 100 miles in 1830 to 1,500 miles in 1840, with a surge to 6,000 miles in 1847 creating the biggest railway network globally1. At 25% of GDP, the amount invested equates to a staggering USD 4 trillion in today’s money, according to Andrew Odlyzko in his book, The Railway Mania of the 1860s and Financial Innovation.

At its height, the bubble saw the formation of hundreds of new railway companies, many of which were based on unrealistic plans for lines that would never be built. Investors poured money into railway shares, driving up their prices to unsustainable levels. The bubble began to burst in late 1845, when a number of factors combined to dampen investor enthusiasm. These included a series of high-profile railway accidents, concerns about the financial viability of many of the new railway companies and a rise in interest rates. The bursting of the railway bubble led to a financial crisis in the UK, and many investors lost heavily. However, the bubble also had a number of positive long-term effects, including the development of a nationwide railway network that helped to boost economic growth.

There is a familiar ring to this moment in history, perhaps most recently incarnated in the Internet boom and bust period of 1999-2002. The capex cycle then was spent on fibre optic cable to build out huge amounts of capacity ahead of expected demand for internet services. Again, the capital spend was of epic proportions. In 1996 fibre optic cable extended one million miles in the US. This surged to 10 million miles by 2000, according to the Federal Communications Commission, with new companies like WorldCom and Global Crossing raising mountains of debt to finance the build. When WorldCom went bust in 2002 it had USD 100 billion of debt; Global Crossing had USD 25 billion. The utilisation rate of networks at the time, according to TeleGeography, was just 20% and by 2010 only reached 30%. Again, irrational exuberance led to limitless capital and debt being made available to build for the future. As with the railroads, while this irrationality was inevitably stamped out with investors losing substantial amounts, the legacy infrastructure enabled the Internet wave to take hold. Short-term pain for irrational investment often leads to long-term gain for disruption.

The big question being asked today is whether the surge in AI infrastructure investment will end up the same way as these previous investment cycles. We believe not; the impact will be far less dramatic, particularly for share prices, but there are some reasons for short-term caution. The introduction of consumer-friendly interfaces such as Bard and Chat-GPT have put access to AI capability within everyone’s reach. This catalyst has led to a surge in infrastructure investment, led by the need for graphics processing unit (GPU) chipsets from Nvidia. Its Q1 earnings report this year reinforced that when it reported one of the biggest USD guides higher of any company in history. The AI arms race was out of the starting blocks and demand had surged. Nvidia is targeting a huge increase in production capacity and Jensen Huang, its CEO, has predicted that USD 1 trillion will be invested in the next four years upgrading data centres for AI. This is supported by research from the Dell’Oro Group that anticipates USD 500 billion of datacentre capex in 2027. Compare that to the level of investment in the auto and truck industry, for example, at an annual USD 33.4 billion (source Wikipedia).

These capex numbers are enormous and in truth no one has any real idea if the capacity will be used or not, or how quickly, but there is a real concern that AI is so important that not investing will entail missing out on a disruptive technology that could be bigger than the Internet was 10-15 years ago. However, the requirement for a sensible return remains. Open AI is said to make about USD 1 billion in revenues and Microsoft has said it hopes to generate about USD 10 billion from its Copilot product. These numbers are small in relation to the investments being made. Sequoia Capital wrote a piece on this recently, suggesting current GPU sales levels of USD 50 billion annually would require at least USD 200 billion of use case revenue to justify the investments. Clearly we are a long way from those levels today.

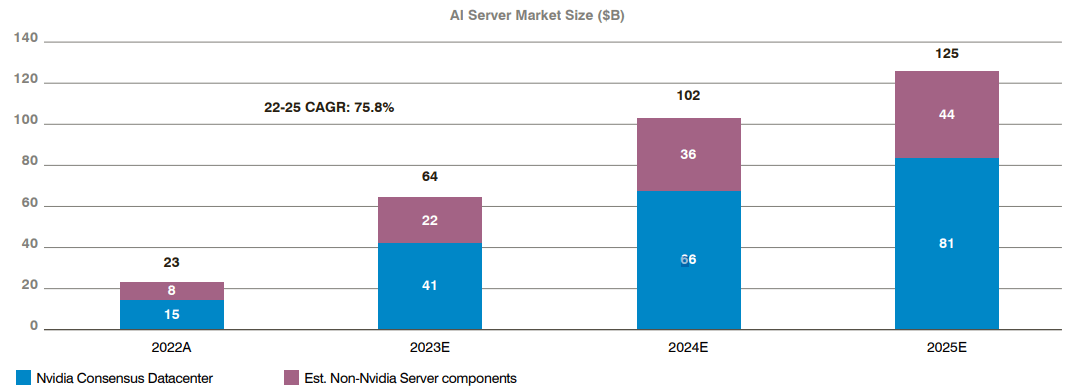

A recent research note from Bernstein attempts to frame the size and scale of investment in AI infrastructure; that demand is shown in the chart below. The implied 75% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) from 2022 to 2025 is totally unprecedented in IT infrastructure cycles and would equate, in 2025, to a build out equal to the total data centre server market existing today. That seems a very tall order – it is worth noting that the average growth rate of the server market has been just 3% compound over the last 25 years according to Bernstein!

AI server market size implied by Nvidia consensus numbers (USD billion)

It is our belief that abundant capital, often from very cash-rich mega-cap technology-driven companies, will drive the build out well ahead of demand, regardless of a possible use case shortage in the early stages. This is not ultimately a bad thing as AI will make significant productivity enhancements to the corporate world, but it is likely to create an air pocket for infrastructure providers. We have seen this for other data centre providers in 2022/23 as ‘data centre optimisation’ has become the buzz phrase for a lack of new investment in capacity. We could easily see a quarter or two where GPU chipset demand drops sharply as existing capacity is digested. This will likely result in a difficult period for the shares of infrastructure providers like Nvidia. As a result, we believe that the next set of investment targets should be more focused on the users of the AI infrastructure rather than the builders of it. This spans sectors across the landscape including healthcare, transportation, retail, financial services and industrials.

The information contained herein is given for information purposes only and does not qualify as investment advice. Opinions and assessments contained herein may change and reflect the point of view of GAM in the current economic environment. No liability shall be accepted for the accuracy and completeness of the information contained herein. Past performance is no indicator of current or future trends. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice or an invitation to invest in any GAM product or strategy. Reference to a security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. The securities listed were selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the themes presented. The securities included are not necessarily held by any portfolio nor represent any recommendations by the portfolio managers nor a guarantee that objectives will be realized.

This material contains forward-looking statements relating to the objectives, opportunities, and the future performance of the U.S. market generally. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of such words as; “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “should,” “planned,” “estimated,” “potential” and other similar terms. Examples of forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, estimates with respect to financial condition, results of operations, and success or lack of success of any particular investment strategy. All are subject to various factors, including, but not limited to general and local economic conditions, changing levels of competition within certain industries and markets, changes in interest rates, changes in legislation or regulation, and other economic, competitive, governmental, regulatory and technological factors affecting a portfolio’s operations that could cause actual results to differ materially from projected results. Such statements are forward-looking in nature and involve a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and accordingly, actual results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Prospective investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on any forward-looking statements or examples. None of GAM or any of its affiliates or principals nor any other individual or entity assumes any obligation to update any forward-looking statements as a result of new information, subsequent events or any other circumstances. All statements made herein speak only as of the date that they were made.