Jian Shi Cortesi, Investment Director, Asia/China Growth Equities, delves into the intricate dynamics of Chinese and Asian equities. She focuses on the impact of manufacturing shifts, India’s emergence and the potential parallels with Japan’s economic trajectory.

20 February 2024

The Chinese equity market has been a cause for concern of late, with underperformance raising eyebrows. While news headlines often attribute this downturn to the perceived weakness of the Chinese economy, a deeper analysis reveals intriguing disparities between China’s GDP growth and its stock market returns. The US has a GDP growth rate of 2.5%, European GDP grew by a modest 0.6% last year, Korea experienced a 1.4% GDP growth, and India’s robust economy surged with a remarkable 7.3% growth. Surprisingly, despite China’s GDP growth of 5.2% over the same period, its stock market declined by 11%. This divergence challenges the conventional wisdom that stock market returns correlate directly with economic growth. Notably, the other major markets mentioned above achieved more than 20% returns, leaving China as an outlier.

When the Chinese equity market falters, analysts often point to the real estate sector. Property bubbles and regulatory changes can significantly affect investor sentiment, but what actually drove Chinese equities down? It was simply the interplay of demand and supply, reflecting the prevailing pessimism about China’s prospects, leading to selling pressure even when GDP growth remains positive.

Manufacturing shifts: A tale of adaptation and economic evolution

The global manufacturing landscape has undergone significant shifts, with companies increasingly moving their production facilities out of China. This phenomenon, often part of the wider trend referred to as ‘decoupling’, raises questions about its impact on the Chinese economy. Will it lead to collapse? Let us explore this through the lens of Nike’s shoe manufacturing journey.

In the 1960s and 1970s, Nike’s shoes were produced in Japan and sold in the US. At that time, Japan was still recovering from World War II and offered cheap labour. However, as the 1980s dawned, production costs in Japan escalated, prompting a shift to Taiwan. Taiwan leveraged its skilled workforce and cost advantages. Yet, as Taiwan’s production costs also rose, the baton then passed to China. The ‘Made in China’ label became synonymous with affordability and efficiency. But China’s own manufacturing costs eventually surged over the past decade, leading shoe manufacturing plants to migrate away from China, even though they remain under Chinese ownership. The new destinations? Southeast Asia and Africa.

Now, let us address the critical question, what happened to the regions left behind as manufacturing shifted? When shoe production exited Japan, did the nation collapse? Far from it. Japan diversified. It transitioned from shoemaking to producing TVs, video equipment, audio recorders and automobiles. Innovation and technology became its forte. As the shoe industry moved from Taiwan to China, did Taiwan suffer an economic downturn? Not at all. Taiwan pivoted towards consumer electronics and semiconductors. It adapted, thrived and continued its economic ascent. Fast forward to today, shoe manufacturing has migrated from China to Southeast Asia and Africa, but China, like its predecessors, is resilient. It is shifting the focus to higher value-added industries, technology, innovation and advanced manufacturing.

The truth is, manufacturing gravitates towards regions with cheaper labour. When it relocates, these regions adapt, evolve and often leapfrog into higher-end production. This cycle propels them from developing to developed status. As the shoe factories move elsewhere, China’s economic story continues, a tale of adaptation, resilience and transformation.

India versus China, who will win?

The perennial debate over whether India or China will emerge as the ultimate winner oversimplifies the intricate dynamics of global economic growth. Why must it be a zero-sum game? History reveals that when one nation rises economically, it need not come at the expense of another. The US ascended without diminishing the UK’s prosperity. Both coexisted, contributing to global progress. Japan’s economic growth did not harm the US. Instead, it catalysed global expansion. China’s rapid GDP growth did not come at the expense of other countries. It fuelled economic expansion worldwide.

Now, India is on an upward trajectory, with its economy thriving fuelled by a young population, technological advancements and market reforms. Yet its rise does not necessitate China’s decline. Instead, consider a scenario whereby low-end manufacturing relocates to India and Southeast Asia. As India’s manufacturing sector flourishes, its citizens gain purchasing power. These empowered consumers can then buy TVs, smartphones and cars made in China. Thus, India’s growth can indirectly benefit China.

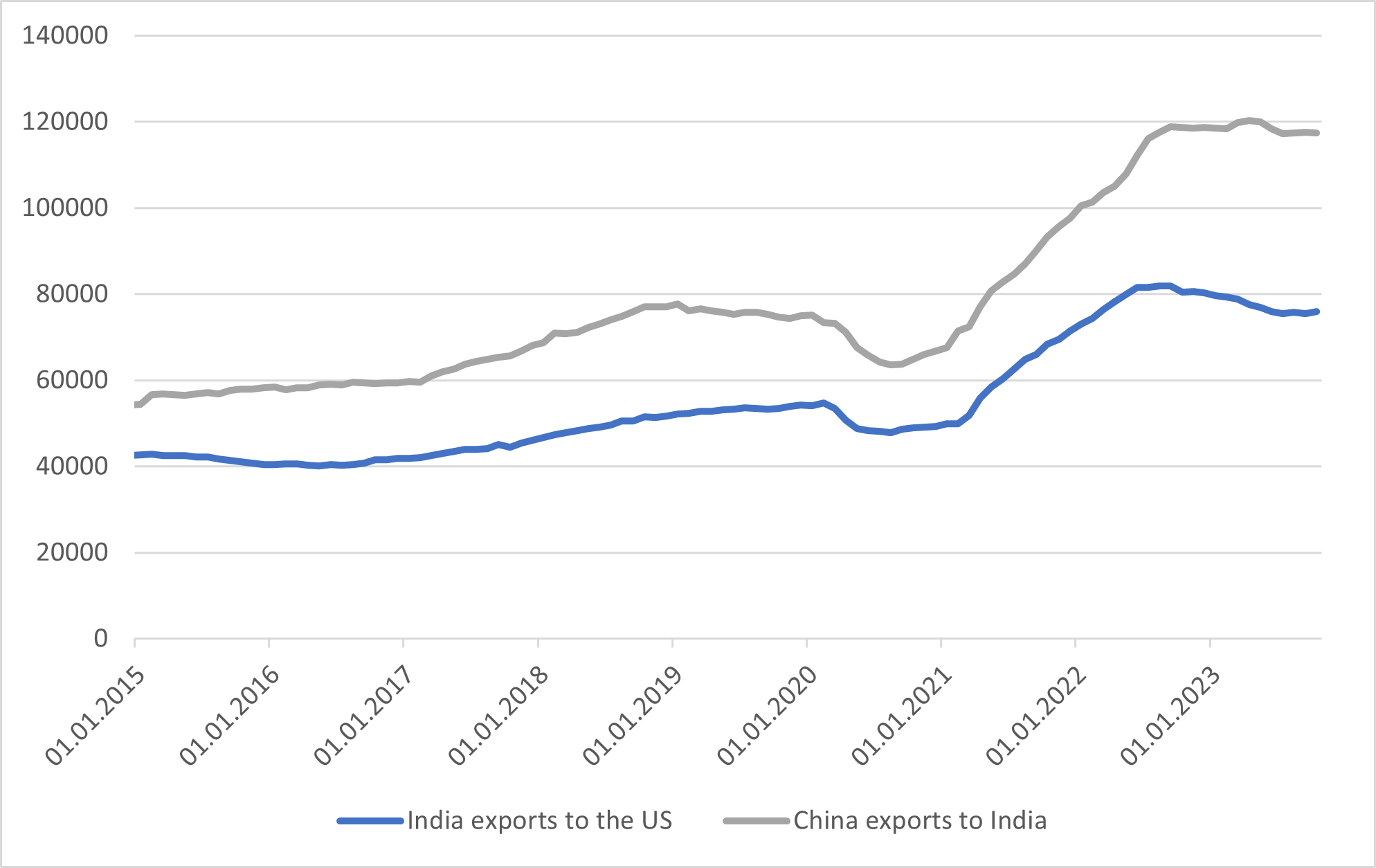

Chart 1: India exports to the US vs China exports to India

Rather than framing this as a zero-sum game, we should recognise that India and China can coexist harmoniously. Their unique strengths contribute to global prosperity. Chart 1 depicts India’s exports to the US surging robustly from 2017 to 2023, the height of trade war discussions and debates on deglobalisation. The grey line shows that China’s exports to India were literally following a parallel path. Consider it a rising tide that lifts all boats. When one nation’s economic prospects improve, it need not come at the expense of another. In this grand narrative, both India and China can thrive simultaneously, contributing to global economic growth.

Navigating the ‘Japanisation’ risk

As the world’s second-largest economy, China now stands at a crossroads, with whispers of a phenomenon ominously dubbed ‘Japanisation’. This term harks back to Japan’s 15-year period of low growth and deflation following the burst of an asset-inflated bubble in the late 1990s.

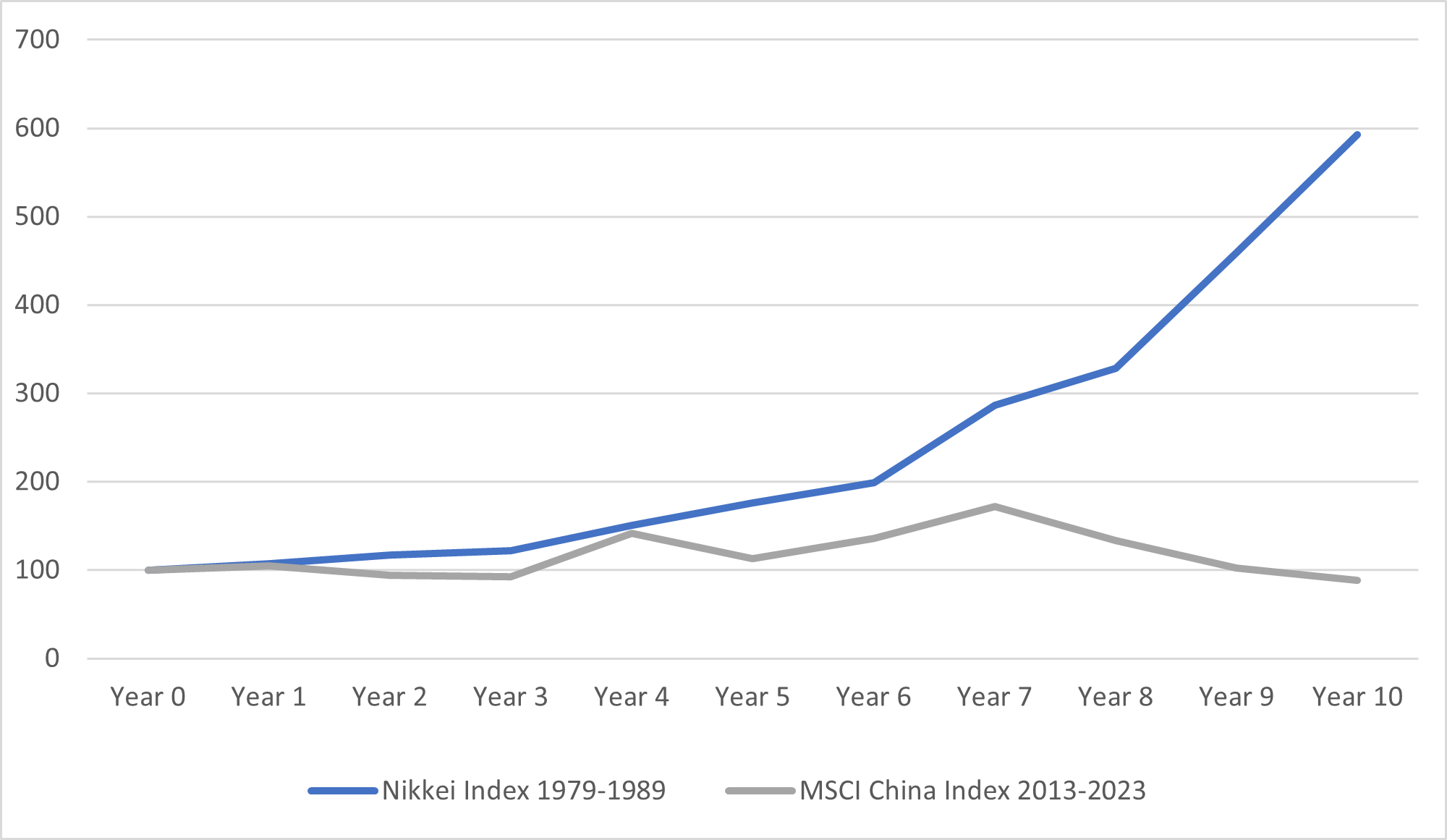

Chart 2: Stock price indices

Before the bubble burst in Japan, Japan’s Nikkei Index soared from 100 to 600 between 1979 and 1989, representing a six-fold increase. The stock market in China (the grey line in Chart 2) follows its own distinct path, with the MSCI China Index rising 8.88% over 10 years, as at 31 December 2023.

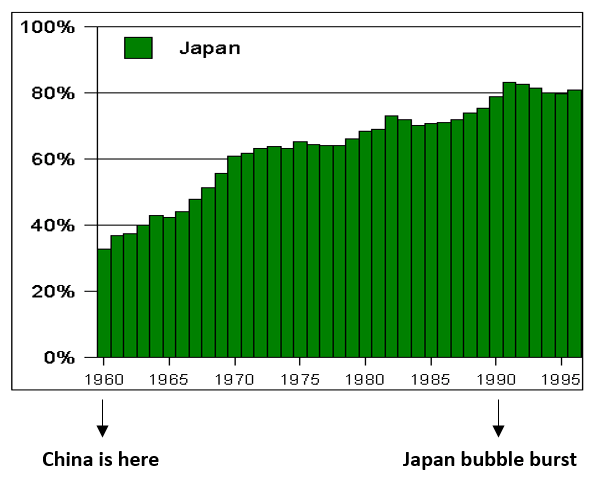

Chart 3: Japan’s GDP (PPP) per capita compared to US

We can rewind history and examine Japan’s development, by comparing its GDP purchasing power parity (PPP) per capita with that of the US. Initially, Japan’s per capita GDP hovered around 30% of US GDP. Over time, Japan’s economy expanded, and its per capita GDP gradually climbed to approximately 80% of the US level. However, in 1990, Japan’s bubble burst, plunging the nation into stagnation. Comparing China’s per capita GDP to that of the US, we find that China’s current per capita GDP is merely about 30% of the US equivalent. The yawning gap underscores that China occupies a distinct developmental stage and is far from a bubble burst similar to Japan’s.

While some draw parallels between China and Japan, we must tread carefully. Their contexts diverge significantly. China grapples with its own set of challenges and opportunities. Assuming that China will inevitably mirror Japan’s path oversimplifies the intricate tapestry of their economic journeys. As the curtain rises, we witness a nation navigating uncharted waters, a story distinct from any that came before.

Redefining China

When discussing China, many foreign investors still harbour the perception that it churns out low-quality, inexpensive products. Foreign investors often associate China with mass-produced, low-quality goods. However, this perspective overlooks the country’s impressive strides in technology and innovation. Success stories from Chinese companies like Lenovo challenge the stereotype, revealing their global presence and technological prowess. Moreover, China’s entry into the commercial flight market with its own large planes underscores its capabilities beyond conventional expectations.

Additionally, China is revolutionising the electric vehicle (EV) space, becoming a major player. European car manufacturers face stiff competition due to China’s supply chain advantage. From battery materials (lithium and cobalt) to battery production, car body manufacturing and electronics, China dominates the EV supply chain. Efficiency and cost advantages give China an edge.

Historically, nations that actively prioritise technology development rarely experience economic decline. Instead, they thrive. China’s relentless focus on innovation and technology leadership positions it for sustained growth. As the country transitions from producing low-quality goods to higher value-added products, perceptions will inevitably evolve. China’s role as a global innovator and economic powerhouse deserves a closer look.

The information contained herein is given for information purposes only and does not qualify as investment advice. Opinions and assessments contained herein may change and reflect the point of view of GAM in the current economic environment. No liability shall be accepted for the accuracy and completeness of the information contained herein. Past performance is no indicator of current or future trends. The mentioned financial instruments are provided for illustrative purposes only and shall not be considered as a direct offering, investment recommendation or investment advice or an invitation to invest in any GAM product or strategy. Reference to a security is not a recommendation to buy or sell that security. The securities listed were selected from the universe of securities covered by the portfolio managers to assist the reader in better understanding the themes presented. The securities included are not necessarily held by any portfolio or represent any recommendations by the portfolio managers. Specific investments described herein do not represent all investment decisions made by the manager. The reader should not assume that investment decisions identified and discussed were or will be profitable. Specific investment advice references provided herein are for illustrative purposes only and are not necessarily representative of investments that will be made in the future. No guarantee or representation is made that investment objectives will be achieved. The value of investments may go down as well as up. Investors could lose some or all of their investments.

The foregoing views contains forward-looking statements relating to the objectives, opportunities, and the future performance of the markets generally. Forward-looking statements may be identified by the use of such words as; “believe,” “expect,” “anticipate,” “should,” “planned,” “estimated,” “potential” and other similar terms. Examples of forward-looking statements include, but are not limited to, estimates with respect to financial condition, results of operations, and success or lack of success of any particular investment strategy. All are subject to various factors, including, but not limited to general and local economic conditions, changing levels of competition within certain industries and markets, changes in interest rates, changes in legislation or regulation, and other economic, competitive, governmental, regulatory and technological factors affecting a portfolio’s operations that could cause actual results to differ materially from projected results. Such statements are forward-looking in nature and involve a number of known and unknown risks, uncertainties and other factors, and accordingly, actual results may differ materially from those reflected or contemplated in such forward-looking statements. Prospective investors are cautioned not to place undue reliance on any forward-looking statements or examples. None of GAM or any of its affiliates or principals nor any other individual or entity assumes any obligation to update any forward-looking statements as a result of new information, subsequent events or any other circumstances. All statements made herein speak only as of the date that they were made.